Abstract

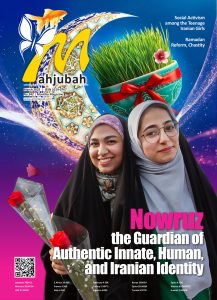

Nowruz, celebrated by over 300 million people worldwide, is one of the oldest festivals in human history, marking the arrival of spring and the renewal of life. Originating in ancient Persia and deeply rooted in Zoroastrian traditions, Nowruz has evolved over millennia, spreading across Iran, Central Asia, the Caucasus, the Middle East, the Balkans, South Asia, and diaspora communities worldwide. Despite regional differences, the festival retains its core themes of renewal, balance, unity, and harmony with nature. Recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, Nowruz transcends ethnic, national, and religious boundaries, bringing people together through shared customs such as the Haft-Sin table, fire-jumping ceremonies, festive meals, and community gatherings. This article explores the historical and cultural roots of Nowruz, its expansion across civilizations, and its role in fostering social unity in both traditional and modern contexts. It examines how Nowruz has adapted across different regions while maintaining its universal themes of rebirth and continuity. Additionally, the study highlights Nowruz’s significance in contemporary global society, where it serves as a symbol of cultural resilience, intercultural dialogue, and ecological consciousness. In a world facing cultural fragmentation and environmental challenges, Nowruz remains a powerful testament to the enduring human need for renewal, peace, and shared heritage.

Keywords: Nowruz, Cultural Heritage, Renewal and Rebirth, Global Celebrations, Unity and Tradition

Introduction

Nowruz, an ancient festival observed by over 300 million people worldwide, is more than just a New Year’s celebration. It is a cultural, social, and historical event that brings together diverse communities through shared traditions and symbolic rituals. Rooted in Persian civilization and spanning across Central Asia, the Middle East, the Caucasus, and parts of the Balkans and South Asia, Nowruz has transcended national and ethnic boundaries, fostering a sense of unity among its celebrants. Recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, Nowruz continues to serve as a bridge between generations, cultural identities, and historical legacies.

Unlike many national holidays that are defined by political or religious affiliations, Nowruz is deeply tied to the natural world, celebrating the arrival of spring and the renewal of life. Its observance on the vernal equinox, when day and night become equal, is symbolic of balance and harmony—both in nature and in human existence. The very name “Nowruz” means “new day” in Persian, reflecting the festival’s theme of fresh beginnings and the universal human desire for renewal and transformation. As Richard Foltz notes, “Nowruz embodies the fundamental human recognition of cycles, change, and continuity—an understanding that transcends cultures and civilizations” (Foltz 68).

For many communities, Nowruz is not merely a date on the calendar but a deeply ingrained cultural experience that strengthens social bonds and reinforces collective identity. Families engage in age-old traditions such as preparing the Haft-Sin table, performing thorough spring cleaning known as “khooneh-tekouni,” and visiting relatives and neighbors to exchange good wishes. The Haft-Sin table, a key element of Nowruz, is set with seven symbolic items, each beginning with the Persian letter “S,” representing prosperity, health, rebirth, and renewal. The placement of Sabzeh (sprouted wheat or lentils) on the table reflects an agricultural past where the festival was closely tied to planting and the rebirth of nature. Similarly, the tradition of Chaharshanbe Suri, where people jump over bonfires, symbolizes purification and the burning away of negativity to make way for a fresh start. These customs, though practiced slightly differently across regions, carry the same underlying meaning of rejuvenation and harmony with nature.

The global recognition of Nowruz as a cultural treasure was formally acknowledged by UNESCO in 2010, when it was added to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The significance of this acknowledgment lies in Nowruz’s ability to foster peace, cultural exchange, and mutual understanding among different nations. Today, the festival is officially recognized as a public holiday in several countries, including Iran, Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan. It is also celebrated by Kurdish communities in Iraq, Turkey, and Syria, as well as among diaspora groups in Europe, North America, and beyond.

As Mary Boyce argues, “Nowruz is not just a Persian tradition; it is a universal festival of life, symbolizing the endless renewal of nature and the enduring spirit of human hope” (Boyce 112). In a world that is increasingly divided by conflict and cultural fragmentation, Nowruz offers a model for inclusivity, resilience, and shared celebration. Unlike many modern holidays that have become commercialized, Nowruz retains its deep cultural and spiritual significance, reminding people of their connection to nature and their shared heritage with millions of others. The communal aspect of Nowruz, from family gatherings to public festivities, reinforces a sense of belonging and collective joy that transcends national and linguistic differences.

The Historical and Cultural Roots of Nowruz

Nowruz’s earliest recorded references date back to the Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE), where it was celebrated as a royal and public festival. The Achaemenid kings would receive dignitaries from across the empire at Persepolis, marking the start of the new year with grand festivities. Nowruz was viewed as a sacred event, aligned with the vernal equinox, symbolizing the balance of forces in the cosmos. Zoroastrian beliefs, which emphasized the struggle between light and darkness, influenced Nowruz as a celebration of renewal and the victory of Ahura Mazda, the god of wisdom and light, over Angra Mainyu, the force of chaos and darkness.

According to Mary Boyce, a leading scholar of Zoroastrian studies, “Nowruz was deeply embedded in the Zoroastrian worldview, as it represented the regeneration of nature, moral purification, and the reaffirmation of cosmic order” (Boyce 45). The festival was not merely a time of feasting but an occasion for spiritual and ethical renewal, a theme that continues to resonate today.

During the Sassanian Empire (224–651 CE), Nowruz became a central imperial festival, blending Zoroastrian rituals with new cultural elements. The Sassanian kings institutionalized Nowruz as an official holiday, emphasizing its significance in governance, social order, and cultural identity. Court chronicles described elaborate festivities, where the king would distribute gifts, grant amnesty to prisoners, and preside over celebrations that reflected the unity of the empire’s diverse peoples. Richard Foltz explains, “For the Sassanians, Nowruz was more than a seasonal change; it was an affirmation of the ruler’s divine mandate, a time when justice, prosperity, and renewal were ritually reaffirmed” (Foltz 78). The festival’s role in strengthening political unity contributed to its widespread adoption across various regions.

With the expansion of Persian influence, Nowruz spread beyond its original cultural sphere, reaching Central Asia, the Caucasus, Mesopotamia, and parts of South Asia. The festival’s adaptability allowed different ethnic and religious groups to integrate it into their own traditions while preserving its fundamental themes of renewal and harmony with nature. In Central Asia, Nowruz became deeply ingrained in Turkic and Mongolian traditions, blending with local customs and agricultural practices. In the Caucasus, Nowruz was embraced by Azerbaijanis, Armenians, and Georgians, who incorporated it into their seasonal festivals. Among the Kurds, Nowruz became a symbol of cultural identity and resistance, particularly in the 20th century when nationalistic movements revived its importance. In South Asia, Nowruz was brought by Persian traders and settlers, influencing the Parsi communities in India and integrating into regional celebrations such as Jamshedi Navroz.

By the time of the Safavid dynasty (16th–18th centuries), Nowruz had become a fully accepted part of Iranian and Persianate cultural identity. The Safavids institutionalized it as a state festival, reinforcing its national significance. Today, Nowruz remains a key celebration in predominantly Muslim countries such as Iran, Afghanistan, and Azerbaijan, highlighting its ability to transcend religious divides.

Despite various political upheavals, attempts to suppress it, and periods of marginalization, Nowruz has demonstrated remarkable resilience. Even during times of colonial rule or ideological restrictions, people continued to celebrate Nowruz as an expression of cultural identity and historical continuity. Today, it serves as a reminder of how ancient traditions can endure through adaptation and community efforts. As UNESCO stated in its 2010 declaration: “Nowruz is a living tradition that has withstood the test of time, bringing together millions across diverse geographies in the spirit of peace, unity, and renewal” (UNESCO, 2010).

Countries and Communities That Celebrate Nowruz

The largest celebrations of Nowruz take place in countries where it is recognized as an official public holiday. In Iran, the birthplace of Nowruz, the festival is the most significant event of the year, lasting for nearly two weeks. The celebrations include setting up the Haft-Sin table, performing spring cleaning (khooneh-tekouni), fire-jumping on Chaharshanbe Suri, and visiting family and friends during Eid Didani. Schools and businesses close during the initial days, allowing families to fully engage in the traditions. Nowruz has been deeply embedded in Persian culture for over 3,000 years, and despite historical and political changes, it remains a cornerstone of Iranian identity.

Afghanistan also observes Nowruz as a national holiday, where it is referred to as “Jashn-e-Nowruz.” The festival is particularly prominent in Mazar-e-Sharif, home to the famous Red Mosque (Rawza-e Sharif), where elaborate ceremonies are held, including the raising of the Janda (sacred flag) to mark the beginning of the new year. Unlike Iran, where Nowruz is largely secular, Afghan celebrations often carry a stronger religious and mystical significance, blending Islamic traditions with Zoroastrian influences.

In Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan, Nowruz is widely celebrated as part of Central Asian cultural identity. These countries were once part of the Persian cultural sphere, and their Nowruz traditions reflect influences from Persian, Turkic, and Mongolic civilizations. In Tajikistan, where Persian is the official language, Nowruz closely resembles Iranian traditions, with people preparing Haft-Sin tables, making Sumalak (a wheat-based dish symbolizing prosperity), and participating in festive games and poetry readings. In Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, large public festivals are organized, featuring horse races, wrestling matches, music performances, and communal feasts. Nomadic influences are more visible in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, where Nowruz is associated with the rebirth of nature, livestock herding, and outdoor festivities.

Beyond Central Asia, Nowruz plays a crucial role in the cultural identity of Azerbaijan, where it is celebrated with great enthusiasm. Azerbaijani traditions include jumping over bonfires, baking special pastries like pakhlava and shekerbura, and setting up ceremonial tables with symbolic elements similar to the Haft-Sin. The Azerbaijani government recognizes Nowruz as a national holiday, and the celebrations are marked by fireworks, public concerts, and storytelling sessions about Dede Qorqud, a legendary Turkic figure associated with wisdom and renewal. Neighboring countries such as Armenia and Georgia also observe Nowruz in certain regions, particularly among Persian-speaking communities and ethnic Azeris.

In the Kurdish regions of Iraq, Turkey, and Syria, Nowruz carries a dual significance as both a cultural and political symbol. For Kurds, Nowruz is not only a celebration of the new year but also a representation of resistance and national identity, particularly in countries where Kurdish cultural expression has been restricted. In Iraqi Kurdistan, Nowruz is observed with mass public gatherings, torch-lit processions, and dancing, often incorporating elements of Kurdish folklore and history. In Turkey and Syria, Nowruz has at times been met with government opposition, as authorities have viewed it as a symbol of Kurdish separatism. Despite this, millions of Kurds continue to celebrate Nowruz as a declaration of cultural survival and unity.

In the Kurdish regions of Iraq, Turkey, and Syria, Nowruz carries a dual significance as both a cultural and political symbol. For Kurds, Nowruz is not only a celebration of the new year but also a representation of resistance and national identity, particularly in countries where Kurdish cultural expression has been restricted. In Iraqi Kurdistan, Nowruz is observed with mass public gatherings, torch-lit processions, and dancing, often incorporating elements of Kurdish folklore and history. In Turkey and Syria, Nowruz has at times been met with government opposition, as authorities have viewed it as a symbol of Kurdish separatism. Despite this, millions of Kurds continue to celebrate Nowruz as a declaration of cultural survival and unity.

In the Balkans, Nowruz is celebrated among Albanian, Bosniak, and Turkish communities, particularly in Albania, Kosovo, and parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The presence of Nowruz in the Balkans is largely due to Ottoman influence, as Persian cultural traditions were introduced to the region through Turkish governance. South Asia also has a historical connection to Nowruz, particularly among the Parsi communities in India and Pakistan. The Parsis, descendants of Persian Zoroastrians who migrated to India to escape religious persecution, continue to observe Jamshedi Navroz, a variation of Nowruz that blends Persian and Indian traditions. The celebration includes lighting ceremonial lamps, visiting fire temples, preparing sweet dishes like ravo, and performing acts of charity. In addition to Parsis, some Muslim communities in northern India and Pakistan also acknowledge Nowruz, largely due to Persian cultural influences during the Mughal Empire.

Nowruz has also become a global celebration in diaspora communities, particularly in Europe, North America, and Australia, where large Persian, Afghan, Kurdish, and Central Asian populations reside. Major cities such as London, New York, Toronto, and Los Angeles host public Nowruz festivals, featuring traditional music, dance, poetry, and Persian cuisine. The ability of Nowruz to unite such a vast and diverse array of communities is a testament to its universal themes of renewal, hope, and togetherness. Whether celebrated in a village in Tajikistan, a Kurdish town in Iraq, an urban center in Turkey, or a diaspora gathering in the United States, Nowruz carries the same message of harmony with nature and the continuity of cultural traditions. The festival’s global reach continues to grow, bridging historical traditions with contemporary realities in an ever-changing world.

Conclusion

Nowruz, as one of the world’s oldest and most widely celebrated festivals, has successfully maintained its cultural significance across centuries, uniting over 300 million people in diverse regions. More than just a new year’s celebration, Nowruz represents a deep connection between humanity and nature, symbolizing renewal, balance, and hope. From its ancient Persian roots in Zoroastrianism to its widespread observance in Iran, Central Asia, the Caucasus, the Middle East, South Asia, the Balkans, and diaspora communities, Nowruz continues to serve as a bridge between historical traditions and modern identities.

Nowruz’s global recognition by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity further emphasizes its importance as a festival of peace, tolerance, and shared identity. As modern societies face increasing fragmentation, Nowruz provides a universal model of inclusivity and cultural continuity, reminding people of the value of tradition, community, and harmony with nature. In a world grappling with challenges such as climate change, cultural divisions, and political conflicts, Nowruz stands as a timeless reminder of renewal and hope. It teaches that just as nature regenerates with the arrival of spring, humanity, too, has the capacity to refresh, rebuild, and strengthen relationships. The enduring nature of Nowruz reflects not only its historical significance but also its relevance in the modern era, offering a powerful example of how ancient traditions continue to inspire and unite people across borders. Whether celebrated in a bustling city in Iran, a village in Central Asia, or a diaspora gathering in North America or Europe, Nowruz carries the same message: a new day, a fresh start, and a collective celebration of life and renewal.

References

Boyce, Mary. Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Routledge, 2001.

Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh, and Sarah Stewart. Birth of the Persian Empire. I.B. Tauris, 2005.

Foltz, Richard. Spirituality in the Land of the Noble: How Iran Shaped the World’s Religions. Oneworld Publications, 2004.

UNESCO. “Nowruz, International Day of Nowruz.” UNESCO, 2010, https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/nowruz-00282.

By: Farnoush M. Goudarzi, MA in Occupational Health Engineering, Urumia Medical University, Tehran, Iran