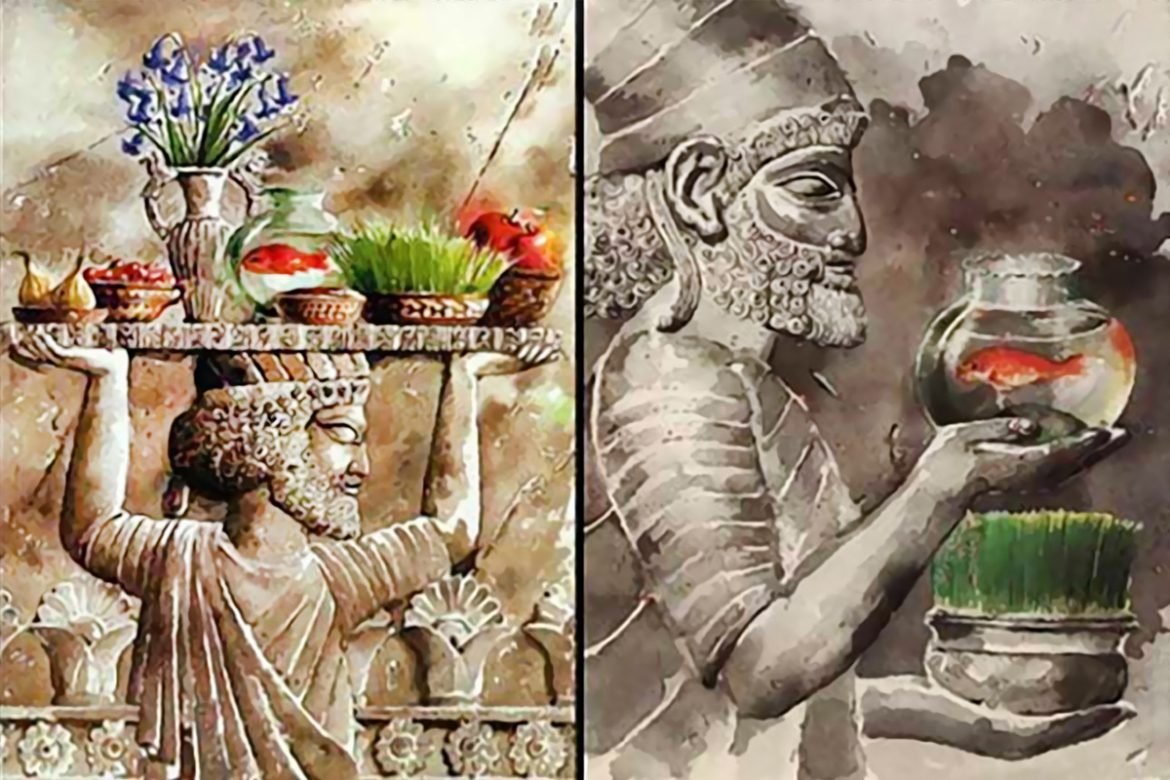

Nowruz is one of the oldest and most significant festivities of the Ajams (non-Arabs, particularly Persians). Throughout the millennia of civilization, it has embodied the ancient customs, religious beliefs, worldviews, spiritual and moral values, and historical and cultural heritage of the Iranian and Tajik people. Across history, especially during critical moments when the cultural essence of the Iranian people was on the brink of annihilation, this ancient festivity played a vital role in preserving culture and civilization while safeguarding national dignity. This mission of Nowruz manifested fully and in all its dimensions during the early centuries of Islam, following the advent of Islam in Persia.

The spread of Islam in Persia created a significant barrier against Zoroastrian fundamentals in all aspects, including the celebration of Nowruz, and brought an end to the religious dominance of Zoroastrianism. However, due to certain factors, the Nowruz festivity did not only survive but also gradually became a widespread tradition across much of the Islamic world.

The first factor was the prominent popularity and humanitarian aspect of Nowruz, which was initially perceived to be opposed to Islamic values by some Arabs. In fact, the festivity of Nowruz has been deeply intertwined with people’s lives since ancient times, embodying joy and happiness, purity and warmth, kindness and benevolence, as well as chivalry and generosity. Such values are universally valid and respected by all tribes and clans, regardless of their religious affiliation. Recognizing the passion and enthusiasm of the people of Greater Khorasan for Nowruz, as well as its inherent virtues, this ancient festivity was ultimately legitimized and permitted following the advent of Islam, despite its portrayal of the Ajams’ ancient mythological and historical traditions.

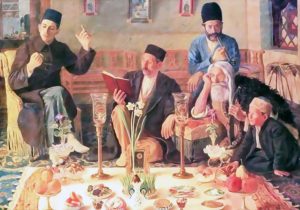

As mentioned by Abu Rayhan al-Biruni in his Asarul-Baqiah (Vestiges of the Past), a tradition portrays the positive view of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) toward Nowruz. Al-Biruni narrates that during Nowruz, a silver plate of halva was offered as a gift to the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). The Prophet asked, “What is this?” They replied, “This is a gift from Persia marking Nowruz.” The Prophet responded by saying, “Yes, Almighty Allah revived the dead and ordered the clouds to rain. Here, sprinkling water became a custom on this day.” The Prophet of Islam then ate the halva and said, “Make every day Nowruz!” (7: PP. 279, 556). In another tradition, it is narrated that on Nowruz Day, some halva was sent to Imam Ali (AS) as a gift. The Imam asked what the occasion was, and his companions replied that it was a Nowruz gift from the Iranians. The Imam then said, “I wish every day was Nowruz for us” (1: V. 11, P. 248).

Undoubtedly, the Ajam continued to celebrate Nowruz even after the advent of Islam. As a matter of fact, the humanitarian aspect of Nowruz, during the early days of Islam, often transcended oppression, enmity, and resentment, inspiring peace, reconciliation, coexistence, and tolerance between the Arabs and Iranians. The evidence for such characteristics of Nowruz is found in a tradition recorded in the book ‘The History of Qom’ in which it is stated that a group of Arabs, led by Abdullah and Ahwas, the sons of Sa’d ibn Malik ibn Amir al-Ash’ari, arrived in the city of Qom on Nowruz in the year 94 AH/712 CE. The governor of Qom received them warmly and invited the leaders of the corps to celebrate this great festive occasion. The culture of Nowruz, which heralds peace and tolerance, prevailed over arms and weapons, and a compromise was reached between the local people and the Arab corps (10: pp. 242–244). This episode best illustrates why Nowruz has endured through ages of tumult; a resilience rooted in the humanitarian essence of this ancient ritual.

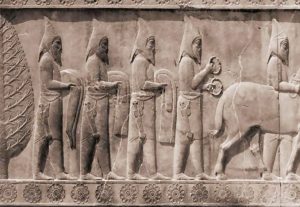

The survival of Nowruz after the advent of Islam in Iran is also linked to its timing, which marks the beginning of the solar calendar. The Persian New Year coincides with the first day of spring and the beginning of the farming season. Since the solar months align more closely with the seasons compared to lunar months, which cycle through all the seasons, it was more practical for taxation purposes. Therefore, the Arabs, whether willingly or otherwise, adopted the solar calendar as the system for collecting taxes and tributes from farmers and regulating the financial affairs of their fledgling caliphate. They relied on Nowruz as the beginning of the cultivation and agricultural cycle. Moreover, since the Arabs lacked sufficient experience in state affairs, Hormuzan, an Iranian frontier governor who had been captured during the battle with the Muslims, played a significant role in implementing crucial fiscal and institutional reforms based on the Sassanid administrative framework. These changes helped establish the first Islamic divan during the caliphate of Umar (634-644 AH/13-24 CE).

Following the establishment of the first Islamic institution, the Arab rulers recognized the significance of the Iranian legal system and sought to preserve certain pre-Islamic governing traditions to benefit the administrative structure of the Islamic caliphate. During the Umayyad rule (133-141 AH/661-750 CE) and particularly after the Abbasid dynasty came to power (750 CE), several divans of tribute were established based on the Sassanid administrative structure. The Ajams (non-Arabs, particularly Persians) were employed, and the responsibility of managing these divans was entrusted to them. This contributed to the spread of Ajam traditions within the administrative structure of the caliphate. As a result, Nowruz, which marked the beginning of the fiscal and agricultural year and is considered a significant Iranian state tradition, was recognized and preserved throughout the caliphate from the early centuries of Islam.

Some customs of Nowruz, particularly the tradition of offering Nowruz gifts, originated from the humanitarian aspect of the celebration and later became part of court rituals. This practice gained considerable prominence in the Islamic Caliphate. As mentioned earlier, several traditions highlight the practice of offering Nowruz gifts to the Holy Prophet (PBUH) and Imam Ali (AS). Even after the advent of Islam, the Ajam continued to observe Nowruz rituals, exchanging Nowruz gifts among themselves and presenting them to uninvited Arab guests. Initially,

this practice was more of an emotional aspect, rooted in the spirit of honoring Nowruz traditions. However, during the Umayyad era, some Arab rulers exploited this tradition to reinforce taxation and replenish their treasury. As a result, the financial dimension of this custom overshadowed its emotional and humanitarian aspects. In his book, Subh al-A’sha, Ahmad ibn Ali Qalqashandi has noted that the first caliph to institutionalize the tradition of Nowruz gift-giving during the Umayyad era was Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, the governor of Iraq (14: V. 2, P. 420), who was infamous for his ruthlessness.

During the Umayyad era, Nowruz gradually became integrated into the fabric of the caliphate, introducing the historical and spiritual values of the Ajam to the broader Muslim community. Since the tradition of Nowruz is deeply rooted in the history, culture, and civilization of pre-Islamic Iran, it is intricately connected to ancient Iranian mythology and legendary kings and heroes, such as Jamshid and Fereydun. It recounts portions of the history of these kings, their battles, and revives the atmosphere that fosters a connection with the spirituality of ancient Iran within the Islamic dominion.

In this context, an Arabic-language poet of Persian origin, Ismail ibn Yasar (d. 132 AH/749 CE), despite the Umayyad’s strong Arab fanaticism, drew upon the glorious history of the Iranians and evoked memorable past events as the central theme of his poems. He skillfully incorporated Persian concepts and spirituality into Islamic poetry.

مَنْ مِثْلُ كَسْرىَ وسابور الجنودِ معا والهرمــــزان لفَــخرِ أو لِتَعظيـم

اُسْدُ ألكتائب يَوْمَ الروع إن زَحفــوا وَ هُمْ أذلوا مُلوك الترك و الروم

“Who can compete with Khosrow and Shapur and Hormozan in decency, greatness, and strain?!

They fight like lions in battle, the lions to which the Turks and Romans surrendered.”

(5: V. 4, P. 423)

Meanwhile, through the efforts of Iranian scholars, the first Pahlavi Islamic works were produced, including a significant book on the history of the Sassanid kings. This book contained illustrations of 27 Sassanid kings, along with their records and advice. It was translated in 113 AH/731 CE for the Umayyad caliph, Hisham ibn Abdul Malik (106-126 AH/724-743 CE), who warmly received it (17: P. 99).

The spiritual and cultural adaptations that emerged during the Umayyad rule preserved the pre-Islamic Persian glory and identity, including Nowruz and its traditions. These adaptations laid the groundwork for the Ajam spiritual movement within an Islamic framework.

Therefore, the Ajam tradition of Nowruz was fully revived, and by the time of Al-Mansur’s ascension to the throne as the second caliph of the Abbasid dynasty (137-159 AH/754-775 CE), it was officially celebrated across the Abbasid state. At the same time, fertile ground was created for the broader Islamic society to become fully aware of Nowruz and its customs. Additionally, a widespread movement to translate Persian Islamic works into Arabic emerged within the Islamic Empire, playing a significant role in preserving and reviving Ajam history, culture, and civilization.

In the book Kitab al-Fihrist, by Ibn al-Nadim and other Arabic reference sources, the names of 25 translators are recorded who translated Pahlavi works into Arabic, introducing the heritage of the Ajams to the Islamic society of that era. Additionally, these sources mention the translation of over 60 historical, literary, and ethical books from the pre-Islamic period into Arabic.

However, the actual number of translations of Ajam works up to the Islamic period must have been significantly higher, as the authors of these sources often did not specify the titles of the works translated. Instead, they simply noted that certain translators had “translated some books from Persian.” Among these translations were important sources of knowledge about the history and civilization of the Ajam, such as Khodai-nameh, Taj-nameh, Ayeen-nameh, Gah-nameh, and similar works, which undoubtedly contained detailed information about Nowruz and its ceremonies. In this context, the first books on Nowruz and Mehregan, exploring the origins and customs of these ancient traditions, were written in Arabic literature by authors of Iranian origin, many of whom were also translators of Pahlavi works into Arabic. One of these books, titled علل اعیاد الفُرس (The Origin of Iranian Celebrations), was written by Zadoyeh ibn Shahoyeh Isfahani (زادویه ابن شاهویه اصفهانی). In his book, The Remaining Signs of Past Centuries (الآثار الباقية عن القرون الخالية), Al-Biruni has cited this work three times, referencing it for information on the old Iranian days and months, the celebration of Nowruz, the month of Shahrivar (the sixth month of the Solar Hijri calendar), and the day of Azar Jashn (3: PP. 70, 282, 289).

Zadoyeh ibn Shahoyeh is also renowned as the translator of Khodai-nameh from Pahlavi to Arabic (7: P. 305). It is certain that Zadoyeh wrote his book on Nowruz and other Ajam celebrations within the same context as Khodai-nameh.

Another translator of Khodai-nameh, Musa ibn Isa Kasravi (second half of the ninth century), also wrote a book titled Al-Niruz and Al-Mehrejan (Arabic version of Nowruz and Mehregan), which served as a reference for the author of Tarikh-e Tabarestan (The History of Tabarestan), citing the story of Zahhak (6: P. 83). It appears that Musa ibn Isa Kasravi regarded both Khodai-nameh and Al-Niruz and Al-Mehrejan as reliable sources of knowledge about the ancient Ajam festivals. Later authors, including Allama Jahiz in Al-Mahasin wal Azdad, and Al-Biruni have frequently cited Kasravi, providing detailed descriptions of Nowruz and Mehregan (7: PP. 231-235; 3: P. 291).

During the same period, another book on Nowruz and other Ajam festivals, titled الاعیاد والنواریز (Festivals and Nowruz), was written by Abulhussain Ali ibn Mahdi Kasravi, an Iranian author (7: PP. 163-164).

Ibn Nadim confirms that another book on Nowruz and Mehregan, titled Al-Nowruz and Al-Mehregan (the same name as the aforementioned book by Musa ibn Isa Kasravi), was written by Ali ibn Harun Munajjem during the same period (7: P. 161). Unfortunately, these four books have not survived, but they made an unprecedented contribution in their time and the following centuries by raising awareness in the Muslim community about the ancient Ajam ceremonies and promoting them in an Islamicized format.

At that time, thanks to the efforts of patriotic Ajams, such books were translated from Pahlavi to Arabic. From the second half of the 8th century onward, Nowruz and other Ajam festivals began to appear in Arabic prose works, which elaborated on the origins of Nowruz and how its customs gained popularity.

As supporting evidence, we can refer to two well-known books that have survived and are attributed to Jahiz, an Arab scholar. The first book is Al-Mahasin wa al-Azdad (Merits and Demerits), which includes a special section titled Mahasin Al-Niruz and Al-Mehrejan (Merits of Nowruz and Mehregan). The author recounts ancient stories about the origins of Nowruz, tracing it back to the reign of Jamshid, and Mehregan, dating back to the reign of Fereydoun. He also explains the customs of Nowruz and concludes this section by mentioning some details about Barbad Khonyagar (the musician) and his songs.

The second book is titled Kitab al-Taj fi Akhlaq al-Muluk (The Book of the Crown on the Ethics of Kings), which draws on Sassanid literature and is regarded as a primary source in the Islamic worldview for researching political and moral thought up to the advent of Ajam Islam. This book includes a special section titled Hadaya Al-Mehrejan wa al-Niruz min Al-Malik wa Lah (Nowruz and Mehregan Gifts from the King and to Him), which explains the custom of exchanging Nowruz gifts between Ajam kings and various classes of society (16: PP. 219-223).

At first glance, the valuable information about Nowruz and its ceremonies in the aforementioned books appears to reflect the pre-Islamic history of this festival. However, it actually represents the revival of Nowruz during the Abbasid era. This is strongly supported by references in the sources that highlight the preservation and observance of Nowruz customs during that period. As Nowruz gained official recognition in the Abbasid era, it was gradually accepted by official religious circles as a celebration that did not conflict with Muslim beliefs. In the works of Islamic thinkers, both Sunni and Shiite, narrations often portray Nowruz as a celebration in harmony with Islamic principles.

Most of these narrations have been compiled by the Iranian scholar Reza Sha’bani in a study titled Nowruz Rituals (13: PP. 158-180). It is worth noting that, due to the perceived harmony between Nowruz and Islamic teachings, this ancient celebration came to be regarded by Islamic scholars as a day marking significant events, such as the beginning of creation, God’s covenant with His servants, the landing of Noah’s ark on Mount Judi, the construction of the Kaaba by Hazrat Ibrahim (Abraham), and the revelation of Gabriel to the Prophet of Islam, among others. These attributed virtues Islamicized the ancient festival of Nowruz and ensured its preservation along with its rituals. In this way, Ajam Nowruz gained Islamic legitimacy and revived not only the specific rituals of Nowruz but also many traditions of Ajam culture and civilization from the pre-Islamic era. The status and significance of Nowruz during that time extended far beyond a mere popular celebration. It represented the essence of Ajam culture within the Islamic context and served as an active factor in fostering intercultural dialogue between the Ajam and the Arabs.

This mission of Nowruz is vividly reflected in the Arabic literature of the Abbasid era, particularly in poetry. Prominent Arabic-speaking poets, including Abu Nuwas (d. 815), Walibah ibn al-Habab (d. 786), Ibn Rumi (836-896), Ibn Mu’taz (861-908), Abu Tammam (788-845), Buhturi (821-897), Hassan ibn Wahab (d. around 850), and others, composed odes praising Nowruz and its rituals. They then presented these poems to the rulers of their time, following the ancient Ajam tradition.

Writing verses about Nowruz became so prevalent in Arabic poetry of that era that the Arabic-speaking Iranian writer, Hamza Isfahani (883-961), compiled a collection of these poems titled Al-Ash’aar ul Sayerah Fi Al-Niruz wal-Mehrejan (Popular Poems Describing Nowruz and Mehregan). Although this collection has not survived, it gained significant fame at the time and was cited and referenced by medieval scholars, including Abu Rihan al-Biruni (3: PP. 51 and 79). The poems composed in Arabic about Nowruz (and Mehregan) served as a cultural bridge, introducing themes and concepts from pre-Islamic Persian-Tajik literature into Arabic prose and poetry. They also acted as an effective means of fostering spiritual and cultural connections between the Ajams and the Arabs.

Following this spiritual dialogue, a new genre of Arabic poetry, known as Nowruziyat, emerged. This marked a transformation in poetic themes, shifting from the repetitive imagery of desert and arid landscapes to vivid depictions of the enchanting beauty of spring and the lush splendor of gardens.

On the other hand, this dialogue played a crucial role in preserving and reviving the traditions of Ajam culture and spirituality within the framework of an Islamic worldview, while also fostering cultural solidarity between the Ajam and the Arabs. As a result, pre-Islamic Ajam history, along with its political and spiritual heritage, gained credibility and significance alongside the values of Islamic civilization. Figures such as Rustam-i Dastan, symbolizing courage; Khosrow Anushirvan, representing justice; and Bozorgmehr Bakhtkan, embodying wisdom—along with other Ajam mythological and historical heroes, many of whom were Zoroastrians—found their way into Islamic Persian and Tajik literature.

Thus, the Arab dominance in Greater Khorasan was ultimately overshadowed by the Ajam cultural influence within the realm of Arab Muslim civilization. There were fundamental differences between these two forms of dominance. The first was established through military force and conquest, while the second was achieved through the power of culture, dialogue, and spiritual harmony. In this transformation, Nowruz played a pivotal role in shaping identity and creating prestige.

Thus, following the spread of Islam in Greater Khorasan the Ajam culture had its influence in the entire realm of Muslim civilization and Nowruz played a pivotal role in shaping identity and creating prestige.

References:

- Al-Isfahani, Abu al-Faraj. “The Book of Songs, Volumes 1-20, Cairo.

- Abu Nawas (1963). “Divan”, Beirut.

- Biruni, Abu Rihan (1352). “The Remaining Signs of Past Centuries’ (الآثار الباقية عن القرون الخالية)”, translated by Akbar Dana Seresht. Tehran: Ibn Sina.

- Zohidov, N.`(2004). “Arabic prose of Persian and Tajik literature in the 8th -9th century”, pp. 45-91.

- Ibn Abi Al-Hadid (1961). “Sharḥ Nahj al-Balāghah”, vol. 11, p. 248, Qom.

- Ibn Isfandiyār (1366). “History of Tabarestan”. Corrected by Abbas Eghbal. Tehran: Kolaleh Shargh.

- Ibn al-Nadim (1973/1393). “Catalog (Kitab al-fihrist)”. Corrected by Reza Tajaddad. Tehran.

- Ibn Hajar (2011). “Manaqib of the Greatest Imam” (al-imâm al-a`zam)”. Prepared by A. Ghiasov and A. Amonov

- Kushajim, Mahmoud Ibn Al-Hassan (1969). “Divan”. Beirut.

- Al-Qalqashandi (1383). Ṣubḥ al-Aʿshá fī Ṣināʿat al-Inshāʾ (‘The Dawn of the Blind’ or ‘Daybreak for the Night-Blind regarding the Composition of Chancery Documents’). Cairo.

- Ali bin Husain Al-Masoudi (1365). “Al-Tanbih wa al- Ishraf”. Translated by Abolghasem Payende. Tehran.

- Mohammadi M. (1364). “Pre-Islamic Iranian culture and its effects on Islamic civilization”, Tehran: Toos.

- Shabani, Reza (2008). “Nowruz rituals”. Dushanbe.

- Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (1352-1353). “Tarikh al-Rusul wa al-Muluk (History of the Prophets and Kings), Vol. 1-15. Translated by Abolghasem Payende, Tehran.

- Jahiz (2003). “Al-Taj fi Akhlagh al-Molouk (The crown in the ethics of kings)”. Beirut.

- Jahiz (1419/1999). “Al Mahasin Wal Azdad (Merits and Demerits)”. Beirut.

By: Dr. Nizomiddin Zohidi, Ambassador of the Republic of Tajikis tan in Iran