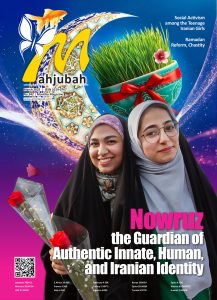

In a world often divided by conflict and strife, festivals offer a much-needed respite. They bring joy, hope, and a sense of community, reminding us of our shared humanity. From the grandeur of Diwali in India to the festive cheer of Christmas around the world, these celebrations offer a glimmer of hope and a chance to celebrate life’s simple joys. Nowruz, the Persian New Year, is one such festival that embodies the spirit of renewal, joy, and family unity.

Rooted in Zoroastrian traditions, Nowruz marks the arrival of spring and is deeply intertwined with themes of well-being, happiness, and communal harmony. The well-being of families during Nowruz is shaped by both historical traditions and contemporary cultural practices. Thus, this essay explores the historical foundation of happiness during Nowruz, the role of Haft-Sin (هفتسین)in promoting family well-being, and how these traditions connect the past to the present through the lens of subjective well-being.

Initially, the concept of happiness and well-being in Persian culture dates back to the Zoroastrian era, where Asha (truth and order) was considered essential for a prosperous life. Zoroastrians believed that celebrating seasonal transitions with joy and gratitude ensured harmony between humans and nature (Boyce, 1979). The Achaemenid and Sassanian dynasties institutionalized Nowruz as a royal celebration, emphasizing generosity, forgiveness, and collective joy.

Historical records indicate that Persian kings held grand Nowruz ceremonies, during which they pardoned prisoners, distributed gifts, and welcomed people from all walks of life into the royal court (Briant, 2002). These practices reinforced communal well-being by promoting social cohesion and renewal. The notion of collective joy and gratitude aligns with modern psychological research, which highlights the positive effects of gratitude and communal celebration on subjective well-being (Seligman et al., 2005).

In addition, a central element of Nowruz celebrations is the Haft-Sin table, which symbolizes renewal, prosperity, and the well-being of families. Each item on the table represents a specific aspect of life and contributes to a sense of balance and happiness:

Sabzeh (سبزه – Sprouted Wheat or Lentils)– Symbolizes rebirth and renewal, encouraging families to embrace new beginnings.

Samanu (سمنو – Sweet Pudding)– Represents strength and patience, reminding families to support one another.

Senjed (سنجد – Dried Oleaster Fruit)– Associated with love and wisdom, reinforcing the importance of emotional well-being.

Seer (سیر – Garlic)– Signifies health and protection, promoting physical and mental well-being.

Seeb (سیب – Apple)– Symbolizes beauty and health, reflecting the value of self-care and familial harmony.

Somāq (سماق – Sumac Berries)– Represents the color of sunrise and patience, reminding families of the value of perseverance.

Serkeh (سرکه – Vinegar)– Stands for wisdom and aging, emphasizing the role of elders in guiding family members.

These symbolic elements serve as reminders of the values that contribute to a family’s well-being, encouraging gratitude, patience, and love. Studies in positive psychology highlight the significance of rituals and traditions in maintaining a sense of identity and emotional security within families (Lyubomirsky, 2008).

Despite modern societal changes, the fundamental essence of Nowruz—family unity and collective happiness—remains strong. In ancient times, families gathered to clean their homes (Khaneh Tekani – خانه تکانی), prepare festive meals, and visit relatives to strengthen social bonds. Today, these traditions persist, with new adaptations such as digital connections enabling distant family members to share Nowruz moments.

Moreover, psychological studies emphasize the importance of cultural celebrations in enhancing emotional resilience and reducing stress (Fredrickson, 2001). Nowruz rituals, including gift-giving and family feasts, provide emotional security, particularly in times of hardship. The act of Did-o-Bazdid (دید و بازدید – visiting loved ones) fosters social support, a crucial factor in mental well-being.

A unique aspect of Nowruz is the tradition of reading classical Persian poetry, particularly the works of Hafez. His verses inspire hope, love, and introspection, fostering emotional and spiritual well-being. Many families practice Fal-e Hafez (فال حافظ), where they randomly select a poem from his Divan and interpret it as a reflection of their fate and aspirations. Some uplifting verses include:

امشب دلم میخواهد که باز سر کنم

آن عاشقی که منزل او مهر و وفا بود

(“Tonight, my heart desires to begin a new

That love whose home was kindness and faithfulness.”)

In addition to poetry, reading the Quran is also a common spiritual practice during Nowruz, offering guidance and reflection on the themes of gratitude and renewal.

In conclusion, Nowruz, with its rich traditions and deep cultural roots, is a celebration of well-being that has endured for over 3,000 years. The festival not only strengthens family bonds but also enhances subjective well-being through communal joy, symbolic rituals, and spiritual reflection. In a rapidly changing world, Nowruz remains a beacon of hope, unity, and renewal, embodying the timeless values that contribute to a flourishing and harmonious society.

Boyce, M. (1979). Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Routledge.

Briant, P. (2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). “The Role of Positive Emotions in Positive Psychology.” American Psychologist, 56(3), 218-226.

Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). The How of Happiness: A New Approach to Getting the Life You Want. Penguin.

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). “Positive Psychology Progress: Empirical Validation of Interventions.” American Psychologist, 60(5), 410-421.

By: Dr. Zeinab Zare