Abstract:

Nowruz, the Persian New Year, is more than a cultural tradition; it is a deeply symbolic ritual that reflects humanity’s timeless connection to nature. Through the lens of mythological and archetypal criticism, Nowruz can be understood as a universal narrative of renewal and rebirth, echoing ancient myths and literary traditions across civilizations. Drawing on Carl Jung’s theory of archetypes and Joseph Campbell’s monomyth, this article explores how Nowruz embodies the cyclical journey of life, death, and renewal, mirroring similar patterns in global mythologies and literature. The festival’s core elements—such as the transition from winter to spring, the symbolic act of cleansing and purification, and the Haft-Sin table—serve as literary motifs that reinforce the human quest for balance with nature. By comparing Nowruz to other seasonal myths, including the Greek story of Demeter and Persephone and various indigenous renewal ceremonies, this study highlights the festival’s role as a cross-cultural model of ecological harmony. Ultimately, the literary structures underpinning Nowruz offer insights into how storytelling encodes environmental consciousness, suggesting that this ancient festival remains a vital paradigm for contemporary discussions on sustainability, cultural resilience, and the human-nature relationship.

Keywords: Nowruz, Archetypal Criticism, Myth and Renewal, Ecological Harmony, Literary Symbolism

- Introduction

Nowruz, the Persian New Year, is not merely a cultural festival but a profound reflection of humanity’s intricate relationship with nature. Rooted in the cyclical rhythms of the Earth, Nowruz serves as a narrative of renewal, transformation, and balance—elements deeply embedded in literary traditions and mythological structures worldwide. From ancient Persian epics to global mythologies, the theme of nature’s renewal has been an enduring archetype in literature and culture. This article explores Nowruz through the lens of mythological and archetypal criticism, focusing on how its rituals and symbols encode a universal message about ecological harmony.

Carl Jung’s concept of archetypes suggests that recurring symbols and narratives in myths and literature are embedded in the collective unconscious of humanity (Jung, 1969). Nowruz, celebrated on the vernal equinox, aligns with the archetype of rebirth and renewal, a theme found in numerous mythological traditions. Joseph Campbell’s theory of the monomyth, or the Hero’s Journey, further emphasizes that human storytelling follows a cyclic pattern of departure, transformation, and return (Campbell, 1949). The seasonal shift in Nowruz mirrors this structure: winter symbolizes stagnation and decay, while the arrival of spring represents rejuvenation and hope.

In Persian literature, Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, often considered the national epic of Iran, is imbued with narratives that align human fate with the rhythms of nature. The myth of Jamshid, the legendary king who is said to have inaugurated Nowruz, signifies the renewal of time and cosmic order. Similarly, Rumi, the 13th-century Persian poet, frequently employed nature as a metaphor for spiritual awakening:

“Be like the spring breeze, carrying life wherever you go.” (Rumi, trans. Barks, 1995)

Nowruz shares symbolic parallels with various seasonal myths across cultures. In Greek mythology, the story of Demeter and Persephone illustrates the Earth’s cyclical renewal. Persephone’s descent into the underworld during winter and her return in spring signify the eternal return of fertility and growth (Graves, 1955). Claude Lévi-Strauss, a structuralist theorist, argues that myths serve as “codes” that reinforce societal values (Lévi-Strauss, 1963). The Haft-Sin table of Nowruz, with elements such as sabzeh (sprouted wheat) representing fertility and apple (sib) symbolizing beauty, functions as a structured narrative that encodes ecological wisdom into cultural practice. Through literary and structural analysis, it becomes evident that Nowruz is not just an Iranian festival but a mythological model of sustainable co-existence with nature.

Similarly, Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey (1949) suggests that all great stories follow a cycle of departure, transformation, and return—a pattern visible in seasonal myths like Nowruz, where the world metaphorically “dies” in winter, undergoes transformation, and is reborn in spring. This universal narrative structure underpins many of humanity’s most enduring stories.

By examining Nowruz through literary and mythological frameworks, we see that it:

- Encodes ecological wisdom into culture, teaching respect for nature’s cycles.

- Functions as a literary and philosophical model for renewal and transformation.

- Connects humanity across civilizations through shared mythic structures.

As the modern world grapples with environmental challenges and cultural fragmentation, the wisdom of Nowruz remains more relevant than ever. It reminds us that renewal is not just seasonal—it is an essential part of human and planetary survival.

As the world faces ecological crises, the literary and philosophical underpinnings of Nowruz offer an alternative worldview—one in which human societies exist in harmony with nature rather than in opposition to it. Scholars such as Vandana Shiva (1997) and Amitav Ghosh (2016) argue that pre-modern ecological wisdom, embedded in cultural rituals and literature, must be reconsidered in contemporary environmental discourse. Nowruz, with its emphasis on cleansing, renewal, and reverence for nature, provides a compelling framework for rethinking the modern world’s relationship with the environment.

- Nowruz and the Archetype of Renewal in Myth and Literature

The seasonal renewal of Nowruz, which represents the transition from darkness to light, barrenness to fertility, and stagnation to movement, aligns with the archetype of rebirth—a pattern found in myths, religious texts, and literary traditions worldwide.

2.1. Nowruz in Persian Mythology: The Legend of Jamshid

In Persian literary tradition, Nowruz is linked to the myth of Jamshid, a legendary king of Iran in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. According to the myth, Jamshid was a just and enlightened ruler who, upon ascending the throne, brought prosperity, order, and peace to the world. His reign was marked by wisdom, divine favor, and the alignment of human civilization with nature’s cycles. One year, on the vernal equinox, Jamshid sat upon a jeweled throne and was lifted into the sky by divine beings. As he shone like the sun, the Earth was rejuvenated, coldness disappeared, and life flourished anew—this miraculous event was marked as the first Nowruz:

“And on that day, the world was bathed in light,

The king of the world brought forth spring’s delight.”

(Shahnameh, trans. Davis, 2006)

This myth represents a cosmic renewal, restoring nature’s balance and ushering in a new era of prosperity. The rise of spring in Jamshid’s myth symbolizes the triumph of light over darkness, aligning human civilization with nature’s cycles. As a cultural and literary archetype, Jamshid embodies the wise ruler who harmonizes his people with natural rhythms. Similar myths across civilizations depict nature’s death and rebirth, reinforcing themes of life’s eternal return, fertility, and cosmic harmony.

- Nowruz in Persian Poetry and Its Connection to Nature

Persian poetry reflects the rhythms of nature, capturing Nowruz’s ecological and spiritual essence. Poets like Rumi, Hafez, Saadi, and Ferdowsi use imagery of spring, flowers, and flowing water to symbolize transformation, renewal, and humanity’s connection to nature. Nowruz is not just a cultural event but a poetic representation of rebirth, deeply embedded in Persian literary traditions. Literature encodes an ecocritical awareness, linking emotions, spiritual awakening, and nature’s revival. In Rumi’s mysticism, Hafez’s romanticism, and Saadi’s moral reflections, spring serves as a literary archetype of renewal, illustrating life’s eternal cycles of death and rebirth.

3.1. Rumi: Renewal as a Spiritual and Natural Force

Jalal al-Din Rumi (1207–1273), one of the greatest Sufi poets and philosophers, often associated the changing seasons with human transformation. For Rumi, spring and Nowruz were not simply external realities but reflections of an inner spiritual awakening. Just as the Earth awakens from the cold grip of winter, the human soul must also shed its burdens and embrace enlightenment.

“Be like the spring breeze, carrying life wherever you go.”

(Rumi, trans. Barks, 1995)

Rumi’s metaphor of the spring breeze signifies purification, renewal, and the transformative power of love and wisdom. The return of greenery, blooming flowers, and flowing rivers in spring mirrors the revival of the soul, urging humans to detach from material stagnation and embrace the spiritual flow of existence. Spring is also a symbol of divine generosity in Rumi’s poetry.

3.2. Hafez: Spring and the Symbolism of Joy

Hafez (1315–1390), one of the most celebrated Persian poets, often uses the imagery of spring and flowers as metaphors for love, joy, and divine beauty. His poetry reflects the literary tradition of Nowruz as a moment of rejuvenation, both for nature and the human heart. In his ghazals, the return of spring is synonymous with the return of happiness, freedom, and the celebration of life.

“Come, let us be reborn like the flowers in spring.”

(Divan-e-Hafez)

This verse captures the essence of renewal, not only in nature but also in the emotional and spiritual realms of human existence. Hafez sees Nowruz as an opportunity to let go of sorrow and embrace the pleasures of life, much like the blooming of flowers after a long winter. His poetry encourages the reader to align with nature’s rhythms, celebrating the beauty of the moment and the cyclical nature of time.

3.3. Saadi: Nature and the Moral Teachings of Nowruz

Saadi (1210–1291), another great Persian poet, approaches Nowruz from an ethical and philosophical perspective. In his book, Gulistan, he reflects on the deep moral lessons nature offers, particularly the ways in which human conduct should mirror the balance and renewal seen in the environment. One of Saadi’s central messages is that just as spring revives the Earth, human beings must cultivate inner renewal by practicing kindness, justice, and wisdom. He frequently compares nature’s beauty and transience to the fleeting nature of human life, urging people to act with humility and awareness.

“The rose does not bloom forever, nor does the nightingale sing without pause.”

(Gulistan, Saadi)

This reminder of nature’s impermanence reinforces the idea that renewal is not merely an external event but a continuous moral and spiritual practice. The coming of Nowruz, in this sense, is not just a festive occasion but an ethical call to introspection, gratitude, and harmony with the world.

3.4. The Haft-Sin Table: A Literary and Symbolic Structure

One of the most profound literary symbols associated with Nowruz is the Haft-Sin table. This carefully arranged display consists of seven elements, each beginning with the Persian letter “S,” representing different aspects of renewal, fertility, and prosperity. Claude Lévi-Strauss (1963), in his studies on myth and cultural symbolism, argues that structured rituals like the Haft-Sin encode cultural and ecological wisdom into tradition. Each element on the table functions as a metaphor for the cyclical nature of life. Sabzeh (sprouted wheat or lentils) represents fertility and the renewal of plant life, emphasizing the connection between Nowruz and agricultural rebirth. Sib (apple) symbolizes beauty and health, serving as a reminder of nature’s nourishing and aesthetic gifts. The apple, often depicted in Persian poetry as a representation of the beloved’s face, further reinforces the literary significance of the Haft-Sin table.

Other elements, such as serkeh (vinegar, representing patience), samanu (a sweet wheat pudding, symbolizing abundance), and sir (garlic, denoting protection against evil), also reflect cultural wisdom and the interconnectedness of human life with the natural world. The Haft-Sin table, much like the poetry of Rumi, Hafez, and Saadi, serves as a literary and symbolic representation of Nowruz’s deeper meanings. Through both poetry and ritual, Persian literary traditions emphasize that Nowruz is not merely a seasonal festival but a celebration of renewal in all aspects of life—physical, emotional, and spiritual.

- Nowruz as a Model for Ecological and Cultural Harmony

Unlike the extractive logic of contemporary societies, where nature is often viewed as separate from human existence, Nowruz fosters a perspective of interconnectedness, emphasizing that human well-being is inseparable from the health of the natural world. Its traditions, spanning thousands of years, reflect an inherent ecological wisdom that aligns with modern principles of sustainability and environmental ethics

One of the most symbolic rituals associated with Nowruz is the practice of spring cleaning, known as “khooneh-tekouni,” meaning “shaking the house.” More than a simple household chore, this tradition represents purification and renewal, both physically and spiritually. Cleaning one’s home before the arrival of the new year is a metaphor for discarding the old and making space for new beginnings, but it also reflects a broader ethos of caring for one’s surroundings. In an age of mass consumption and environmental degradation, this practice serves as a reminder of the importance of mindful living and reducing waste, reinforcing a sustainable relationship with the environment.

Another ecological tradition within Nowruz is the ritual of growing sabzeh, or sprouted wheat, barley, or lentils. The act of nurturing a small patch of greenery symbolizes renewal, fertility, and the human connection to the Earth. At the end of the celebrations, the sabzeh is typically released into running water, signifying a return to nature and the continuous cycle of life. This act reinforces an ancient understanding of sustainability—one that respects the Earth’s natural rhythms rather than disrupting them. The symbolism of sabzeh aligns with modern ecological movements that advocate for a return to organic and regenerative agricultural practices.

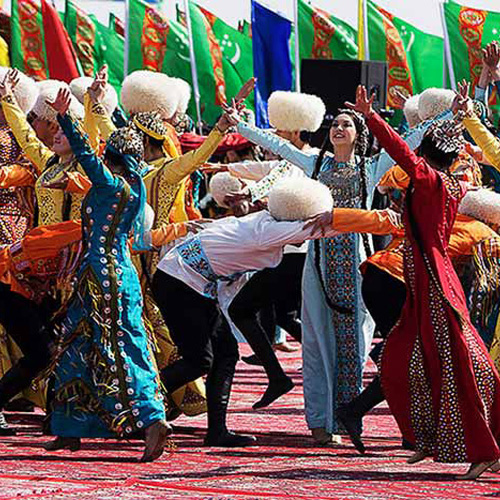

Fire-jumping, or “Chaharshanbe Suri,” is another key tradition that carries both ecological and symbolic meaning. During this festival, people leap over bonfires, chanting phrases that express a desire to rid themselves of negativity and absorb the strength and warmth of the fire. While this may seem like a purely cultural practice, it holds deeper environmental implications. Fire, in many ancient traditions, is viewed as a purifier, capable of cleansing both the body and the land. In a broader sense, this ritual reminds participants of the power of natural elements and the importance of maintaining a respectful relationship with them.

- Conclusion

Nowruz, the Persian New Year, symbolizes a universal theme of renewal, as reflected in mythological narratives like Jamshid’s story in the Shahnameh, akin to myths of Demeter and Persephone, and Osiris. Persian poets such as Rumi, Hafez, and Saadi use springtime imagery to convey themes of spiritual rebirth and personal transformation. Beyond literature, Nowruz traditions like growing sabzeh, fire-jumping, and spring cleaning promote ecological harmony, sustainability, and respect for nature. The Haft-Sin table further embodies ecological wisdom through its symbolic elements. Thus, Nowruz transcends cultural boundaries, offering timeless lessons on living harmoniously with nature and embracing life’s cycles of renewal.

- References

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press, 1949.

Davis, Dick. Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings. Penguin Classics, 2006.

Ghosh, Amitav. The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable. University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths. Penguin, 1955.

Jung, Carl G. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press, 1969.

Hafez. The Divan of Hafez. Translated by Reza Saberi, Ibex Publishers, 2002.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. Structural Anthropology. Basic Books, 1963.

Rumi, Jalal al-Din. The Essential Rumi. Translated by Coleman Barks, HarperOne, 1995.

Saadi. Gulistan. Translated by Wheeler M. Thackston, Ibex Publishers, 2008.

Shiva, Vandana. Biopiracy: The Plunder of Nature and Knowledge. South End Press, 1997.

By: Mehrdad Moazami – PhD. in Persian Language and Literature